London’s relationship with eels is one of those wonderfully slippery stories that wriggles through every era of the city’s past, from medieval tax ledgers to East End pie shops.

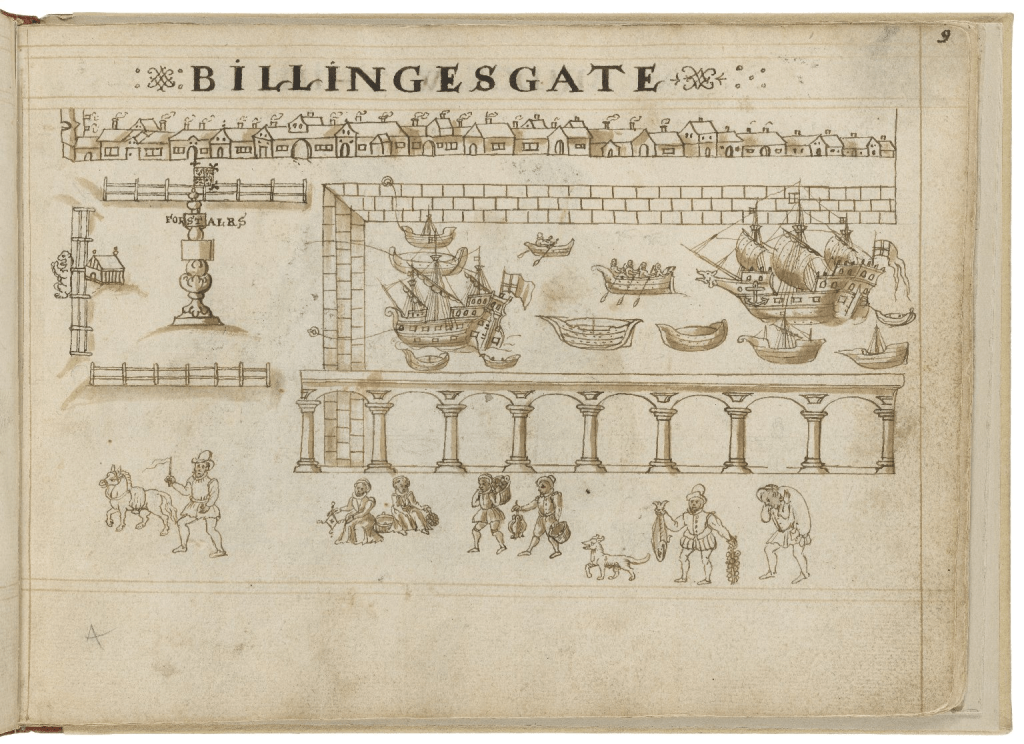

It began innocently enough for me while digging into the history of Billingsgate Fish Market, where I stumbled on a curious quirk of the 1699 Act of Parliament. The Act declared Billingsgate a “free and open market” for all fish… except eels“, which were reserved for Dutch fishermen working the Thames. This wasn’t protectionism, it was gratitude. After the Great Fire of 1666, Dutch eel‑boats fed a starving London, and the city repaid the favour with a monopoly on catching and trading the eels.

The Dutch sold live eels from ships on the London Thames for 600 years, only leaving in 1938. But by the 1930s they weren’t transporting eels in these ships anymore. The ships stayed parked on the Thames as an antiquarian storefront & the Dutch refilled them from modern tankers.

But that little footnote opened the door to a much deeper eel‑shaped rabbit hole that I went down. In medieval England, eels weren’t just dinner, they were a cornerstone of the economy.

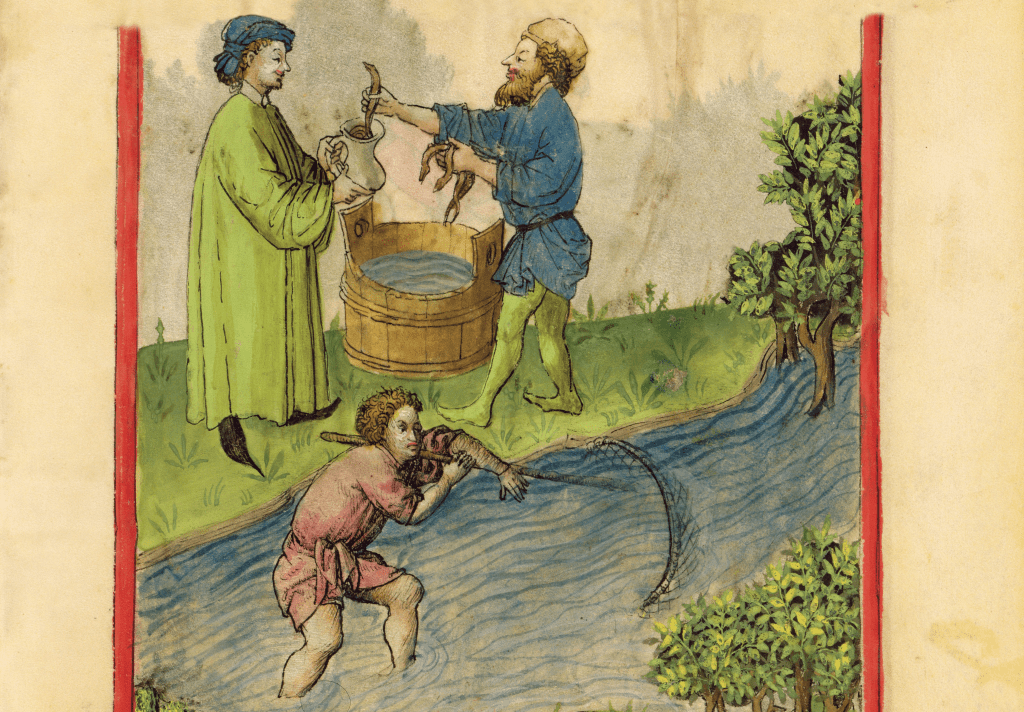

Medieval England’s rivers were so thick with them that rents, taxes, and fines were routinely paid in “sticks” of eels. There were 25 eels in a stick, likely because 25 was the number that could be smoked on one stick at a time. Ten sticks made a “bind”.

Records show more than half a million eels changing hands annually in the 11th century alone. One abbey demanded 60,000 eels a year from its tenants. Prices were often quoted in eels rather than coins, because eels were more stable than currency and far easier to collect. There was a roaring trade in eels across the British Isles, where they were found in huge quantities. In 1392, King Richard II cut tariffs on eels in London to encourage merchants to trade them there.The implementation of such measures suggests that the eel trade was viewed as a mark of a booming economy and had beneficial knock-on effects more widely.

The ecological backdrop mattered too. England’s waterways teemed with European eels, making them a reliable, renewable resource. And with the medieval religious calendar banning meat on roughly a third of the year’s days, fish, especially eels, became essential.

As theologians liked to argue, fish didn’t inflame the passions the way beef or pork supposedly did. Thomas Aquinas even suggested that animals like cows stirred carnal thoughts, while fish were safely neutral. Eels, despite their shape, were considered the least “lusty” of all.

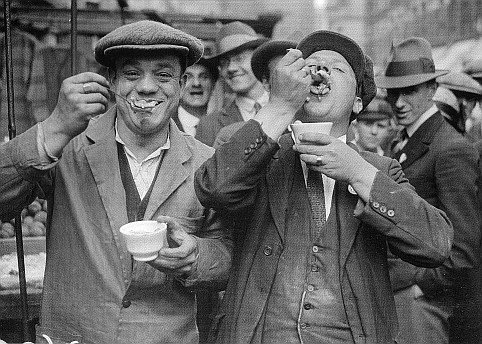

Fast‑forward to the 18th and 19th centuries and eels became London’s fast food. Street vendors sold eel pies from portable ovens, and jellied eels became a staple of working‑class diets. By the 1920s, eel stalls were as common in the East End as chip shops are today.

But as tastes shifted in the late 20th century, the dish retreated to coastal towns and a handful of traditional pie‑and‑mash shops.

From medieval currency to modern curiosity, from Dutch eel‑boats to jellied eels in blue‑and‑white bowls, London’s eel story is anything but dull.

Well, who knew that in the 17th century, Dutch eel‑boats fed a starving London? Interesting bit of history

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s strange that tis once so-popular dish is now largely regarded with suspicion. I’ve never eaten eels, and wouldn’t know where to start!

LikeLike