I shudder for using the much vaunted term “Hidden Gem” so beloved of social media influencers. No, I’ll stop there or this piece will just become a diatribe of scorn and derision. Everyone’s entitled to their opinion.

However when I wanted a short phrase to some up the building I want to describe I couldn’t get past the term. St Etheldreda’s Church in Ely Place adjoining Hatton Garden should be on everyone’s to do list. Not because it’s the largest, or most beautiful, or the oldest church in London, to be honest it’s not any of those things. However from a storyteller’s perspective it’s got everything.

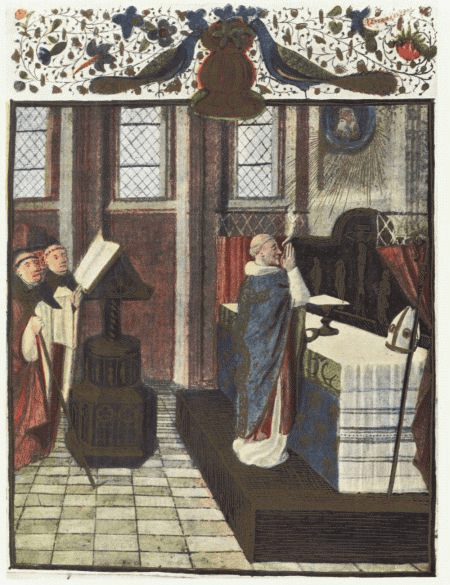

Built between 1250 and 1290, it was originally the chapel for the London palace of the Bishops of Ely, which is were Ely Place comes from. Like all churches back then and for the next three hundred odd years it was Catholic. The saint it’s dedicated to, Etheldreda was born in the 7th century and was in turns, princess, wife, queen, nun and abbess, enjoying every possible position of power a woman could claim in early Anglo-Saxon England.

There’s a shrine and statue to her inside the church, as well as a relic, supposedly her hand, which is kept in a very ornate box, but not on display. Good enough you might think, but the church keeps on giving. Apparently it was the location for secret meetings between Henry VIII and Thomas Cranmer around 1532. It is said that the monarch used Cranmer as a sounding board for the proposed split from Rome and the tricky problem of Henry’s divorce from Queen Catherine. Cranmer proved a most useful confidant, so much so that he found himself elevated to Arch Bishop of canterbury in 1533. However, Cranmer came to a sticky end as when Henry’s daughter Mary took the throne after the Death of Edward VI he was burnt at the stake for heresy. The church reverted back to Catholicism until Elizabeth I took the Crown.

It seemed that there was a degree of stability for the church and it continued along without much incident until the time of James I, 1623 to be exact, the afternoon of 26th October to be precise. For some reason in 1620 part of the church had been let to the Spanish ambassador, a man called Count Gondomar to use as a private chapel.

The Count, being a Catholic, therefore put St Ethelreda’s in the strange position of being a dual denomination church. The reason this was allowed was that foreign diplomats were given the freedom to openly follow their Catholic faith and to celebrate the mass in private chapels.

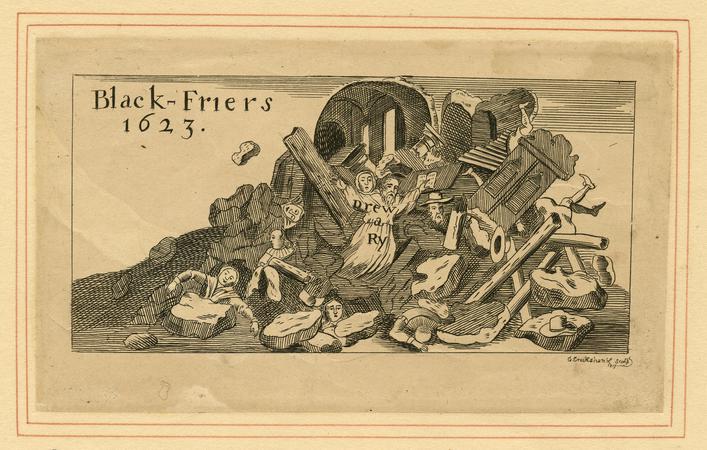

This was meant to extend to their immediate family and possibly some of those in their entourage, but these rules were regularly broken and quite a large congregation could assemble. On the day in question Robert Drury, a celebrated Jesuit preacher was in town to deliver a sermon. Had it just been for the ears of the Count and his family, it would have undoubtably been delivered in the Catholic part of St Ethelreda’s, however the numbers that look set to attend were way beyond what the Count could cram into his private chapel, and also he possibly thought he wouldn’t get away with such a flagrant flouting of the rules governing the Catholic mass. So he made advances to use Hudson house in Blackfriars, which was the residence of the absent French Ambassador. A decision that would have dire consequences.

Hudson House enjoyed the same status as the Count’s chapel at St Ethelreda’s, as long as it was a private worship it would be ok. Bringing in 300 guests was rather stretching the boundaries. The excited congregation assembled in the upper rooms of the house and settled down to hear Drury speak. If the rules could be stretched, then the floors of the rooms could not be elasticised to contain the weight of all assembled and minutes into the sermon the floors started to give way.

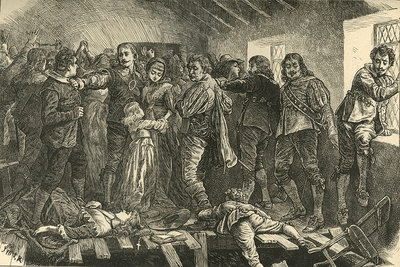

With an ear slitting crack the floor collapsed, sending the crowd crashing to the storey below. That level, too, collapsed, until hundreds of broken bodies came to rest in the Ambassador’s withdrawing room on the ground floor. Accounts from survivors say that the noise from the injured and dying, “Came like the wailing at the gates of Hell”

Accidental death on this scale had never happened in London before. Ninety-five people lost their lives, among them Drury himself and also fellow priest William Whittingham. Many more would have sustained what today we would call life-changing injuries.

What happened in the aftermath of the disaster is mixed dependent on which side of the religious divide people sat. Protestant accounts say that help was quickly on hand from a party of workman that had been building walls on an adjoining property, and that many bystanders rush to deliver help to those in the rubble. Those of a Catholic leaning reported that many onlookers assembled, “and being grown savage and barbarous, refused the injured any water and instead mocked them with taunts and gibes.”

Whatever side you chose to believe, over the next few weeks the majority of publications in the city seized upon the catastrophe as a sign of divine judgement against Catholics. One article started, “So much was God offended by their detestable Idolatries,” while another coined the phrase “The Fatal Vespers”, which is how the calamity is known today.

Nineteen of the dead were brought back to St Ethelreda’s for burial in a section of the crypt specially arranged by Count Gondomar, who escaped without injury. The inference being that they were either part of his immediate family or members of his staff.

Goodness, what a horrific tale. I’m quite surprised it’s not more widely known.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’d been in the church a couple of times and never noticed the plaque. Saw it last week and found out about the story.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Gosh that’s a jolly good tale.

LikeLike