The title of this piece comes from one of my favourite 20th century authors, Jack London. The whole quote is “A bone to the dog is not charity. Charity is the bone shared with the dog, when you are just as hungry as the dog.“

Now this piece is not about bones, dogs or American authors, it relates to a story I’ve just found concerning charity, laudable philanthropy and those that tried their best to thwart those plans.

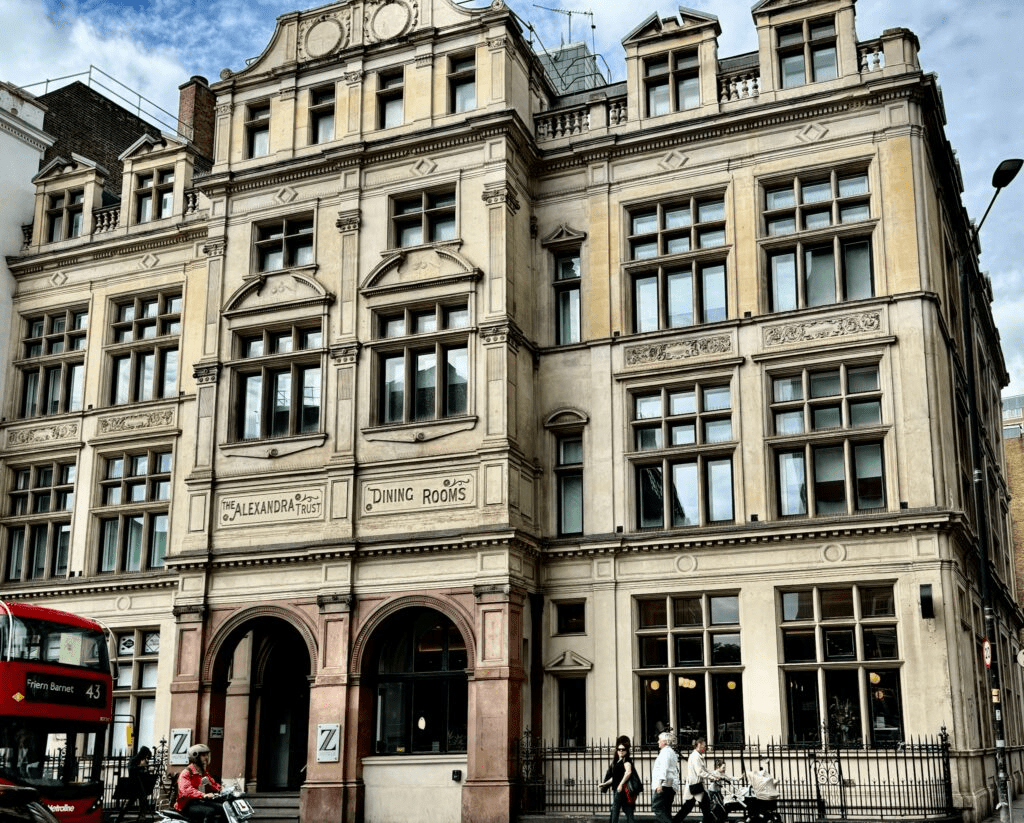

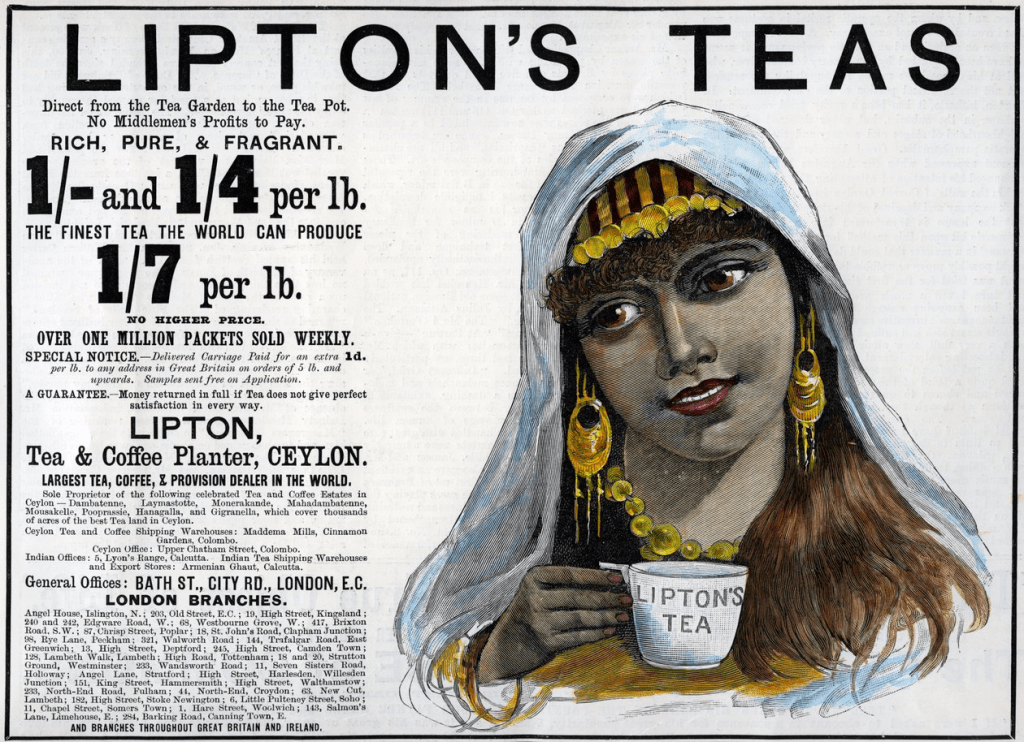

On the City Road, just a few steps away from the renowned Moorfields Eye Hospital stands a rather handsome building, delightfully incongruous amongst the columns of glass, steel and concrete that demarks the beginning of the area of Old Street. It is known as Empire House.

Today still known by the same name it is home to the budget chain Z Hotels, but if you look at the picture you will see that above the entrance is the wording The Alexandra Trust Dining Rooms.

Let me in introduce two of the main players of this story, who happen to be the good guys.

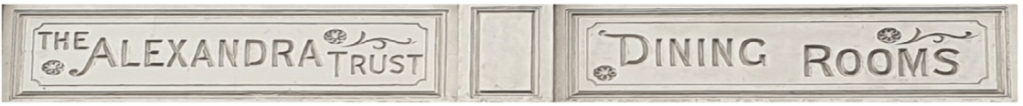

First is Sir Thomas Lipton, wealthy grocer, philanthropist and the owner of a rather fantastic moustache. His name is best known today in conjunction with the tea that he sold. He claimed that his secret for success was selling the best goods at the cheapest prices, harnessing the power of advertising, and always being optimistic. These principles were to be sorely challenged over the course of this story.

The second player is Her Royal Highness Princes Alexandra, at the time Princess of Wales and wife of the future King Edward VII. During the late 1890s, her “Thing” as far as royal patronage was concerned revolved around food, ostensibly the provision of free meals to schoolchildren in the poorest areas of the nation. This made her an ideal figurehead for the scheme that Thomas Lipton dreamt up, but as we’ll see later it didn’t mean that she was in complete touch with the lower classes.

Lipton was the epitome of the Victorian self made man. Born in 1848 in a run down tenement in the Gorbals in Glasgow he had known hardship and hunger from an early age. Lipton’s parents had been forced to leave Ireland due to the Great Famine of 1845, moving to Scotland in search of a better living for their young family, but his father struggled to find regular work. Thomas’ siblings, three brothers and one sister, all died in infancy leaving just Thomas and his parents. By the 1860s things had taken a turn for the better and the Liptons had started a business selling ham, butter and eggs.

Tommy, as he was known left school at the age of thirteen to supplement his parents’ limited income, and found employment as a printer’s errand boy, as well as working in the family business. He had always been captivated by the sea and in 1864 signed up as a cabin boy on a steamer and later travelled to America where he spent five years, Returning to Glasgow he opened his own store, Lipton’s Market in Glasgow and within a decade had store across Scotland and later across the whole of the UK. He quickly spotted the demand by the middle and lower classes for tea and made the most of judicious buying in a falling market to secure massive stocks which he sold cheaper than his competitors.

And so we fast forward to the time of the story 1898. Tommy Lipton, now a millionaire is very aware of the plight of many Londoners. He has concerned himself with many philanthropic projects over the years, but feels it’s time to make a mark himself. Using all his media savvy he assembles members of the press for an announcement.

He outlines his plan to provide cheap meals at cost price in a series of counter-service restaurants in the poorest parts of London. and is prepared to spend £100,000, that’s around £11 million in todays money, on building them. The project has Princess Alexandra as it’s Patron and builds upon her Diamond Jubilee meals for the poor project launched the previous year, for which the then Mr. Lipton had donated £25,000 of the required £30,000, and which succeeded in feeding 300,000 people. It can be no coincidence that Tommy becomes Sir Tommy later that year.

Fighting poverty was a very fashionable cause among late Victorian royalty and high society, but those with vested interests in the supply of food are not so happy with Lipton’s plans. There are shall we say rumblings of discontent in the form of letters to the Times and other newspapers expressing concerns that removing thousands of people from the bottom of food supply chain will impact the businesses of those that earn a crust by supplying cheap (and probably unwholesome) food. The newspapers quick realise that this is a far more sensational story and start to give these dissenters a voice.

St. James’s Gazette worries that the scheme, with its proposed marble tables, courtyards, fountains, shrubs and lunch for 2ᵈ, will put coffee houses out of business. Princess Alexandra receives a petition from the London Coffee and Eating-House Association, suggesting she has been misled by Sir Thomas and the scheme is not a charitable endeavour but a business proposal. The Gazette later reports that the London Master Bakers Protection Society has petitioned the Privy Council to refuse a royal charter for the newly constituted Alexandra Trust.

The furore spreads beyond the capital with the Times publishing an article that criticises the scheme for being liable to create a dependence among ‘this class’ on charity, due to the pernicious habit of indiscriminate alms-giving. The idle poor, drunk brutish husbands, the consumption of drink and debauched pleasure seeking also feature heavily in the piece penned by Mr J. Henry Griffith. Mr Griffiths is chairman of the Birmingham Charity Organization Committee.

Over the next year the story is seldom off the pages of the nations newspapers and taking a swipe at the project seems to have developed into a national sport. Lipton by now desperately trying to manage this negative situation plumps for the least aggressive of his critics, the Illustrated London News to attend the grand unveiling of the first dining room, Empire House, 136-144 City Road.

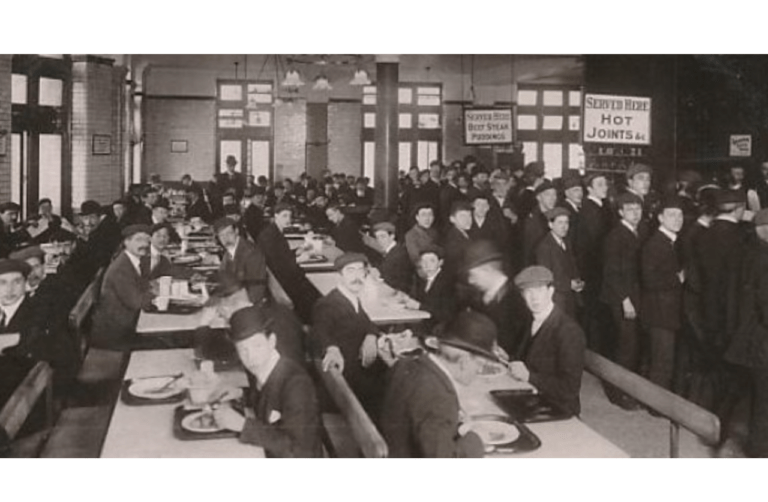

The report states that the building has three floors of dining rooms each designed to hold 500 people. Kitchens are on the top floor and that 1,200 steak puddings can be cooked in it’s ovens simultaneously. There are ‘electric automatic lifts’ to aid distribution of food to the dining floors, and a bakehouse with electric kneading machines. The entrance hall and staircase are both stylish and utilitarian, with shrubs, mosaic flooring and stone columns (but no fountains). The facade is in Bath Stone with the entrance in red Aberdeen granite. Soup, steak pudding with two vegetables and a pastry costs 4½ᵈ. The Sketch who were probably less than happy to not get the scoop describes the establishment as a type of slap-bang, an archaic noun meaning a low eating house.

Customers pay at a kiosk situated in the entrance hall. Handing over their 4½ᵈ they receive a token in return and exchanged it for food in the dining areas. Shortly after opening Princess Alexandra makes an official visit, She queues with the other customers, obtains her tokens and seats herself in one of the Ladies dining rooms as house rules stated that men and women should not mix while eating! The Illustrated News reports that she opts for soup, steak pudding and plum duff. “However, she takes only a mouthful each of the first two and none of the last“crows the author, snidely implying that a meal produced for such a low price must be of a similarly low quality. It also goes on to trumpet that the Princess is shocked and disturbed to be told by the manageress that it is the habit among the lower classes to wash only after a meal and not before.

Despite all the negative press the dining rooms were tremendously popular with the masses. It was ideally placed just 100 metres north of the Old Street/City Road junction, the meeting point of a number of tram routes and so was very accessible.

Empire House continued to serve hot meals right up until the late 1940s although by then in a reduced capacity and closed in 1951. Sir Thomas Lipton died on the 2nd of October 1931. A lifelong bachelor, his will consists mainly of bequests to charities, hospitals and other deserving organisations, many in his native Glasgow. Staff at the Alexandra Trust send a wreath to his funeral, but the Trust is not mentioned in his will. Possibly he was worn down by the negative reaction to his laudable project, as despite Empire House’ success the plans for a chain of similar establishments around the city never came to fruition.

Another interesting story, showing us how little has changed in the ways ome people think in the intervening century.

LikeLiked by 1 person