Paul Pindar was born in 1565 the second son of Thomas Pindar of Wellingborough, Northamptonshire. He was educated at Wellingborough School with a view to him studying at Oxford. During his school years, his father recognised that young Paul was “rather inclyned to be a tradesman”, so decided to apprentice him to a London merchant Henry Parvish rather than send him to Oxford.

When Pindar had turned eighteen Parvish sent him to be his factor at Venice. Pindar remained in Italy for about fifteen years, and by trading on commission and on his own account acquired “a very plentiful estate.“ In 1602 it was rumoured that he was acting as a banking agent in Italy for Queen Elizabeth’s Secretary Robert Cecil, who “feared to have so much money in England, lest matters should not go well“. This was during the last year of Elizabeth’s life and Cecil was hedging against civil unrest should the replacement for the throne not be greeted favourably in England.

He was appointed as secretary to the English ambassador in Constantinople in 1611, eventually becoming ambassador himself, before returning to England around 1622 when he was knighted by James I. His philanthropic work in the last twenty or so years of his life saw him donate money to many charitable causes.

A Pamphlet of the time records that he was “renowned for his generosity in educating young men at his own ‘care and cost’” it also states that Pindar saved the life of a felon named Running Jack who had been sentenced to death. The prisoner “was found to have bin such a notorious Malefactor, that the Bench did condemn him to dy: but hee hath since obtained a Reprieve by the means of Sir Paul Pindar.“ sadly it doesn’t state what crimes Running Jack had committed.

He also supported the monarchy with loans of money and precious jewels, something that was to be a problem a number of years later and in 1644 donated 1,705 lbs (775 kg) of gold to help the escape of Queen Henrietta Maria and the young Charles II to the Netherlands.

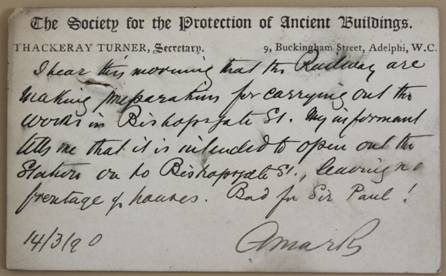

With his amassed wealth, Pindar built himself a grand residence on Bishopsgate with a street façade of three and a half storeys and a garden with views of Moorfields and Finsbury Fields. Houses of several storeys with jettied fronts were not rare in London in 1600, but Pindar’s house would have been unusually large and the façade particularly striking. The house escaped the Great Fire, but was demolished in 1890 as part of Liverpool Street station expansion. However part of the building can still be seen as someone with some foresight removed the facade and donated it to the Victoria and Albert Museum.

There was a plan to incorporate the front elevation of the building into Liverpool Street station’s facade, but sadly the opportunity was missed which would in my mind have done wonders for the boring front entrance. Before its demolition the house had become the Sir Paul Pindar Tavern

Pindar died on 22 Aug. 1650, and was buried with some pomp at St. Botolph’s, Bishopsgate which was next to his mansion. In his will he left legacies and charitable bequests amounting to £12,000 (£1m) to various hospitals and prisons in and near London. Given the perception of his wealth, this seems quite a low figure, however his total estate was never realised. It was estimated that there was in total £180,000 (£14m) outstanding in what were termed as “Desperate Debts“. These were debts run up by James I, Charles I and Charles II, other noblemen and the Exchequer that were never repaid to Pindar.

Had these extravagant monarchs actually repaid their debts his charitable bequests and donations to the City would have been far larger than they were, and possibly Pinder would have become as well known as that other London benefactor, Richard Whittington.

What interesting stories you unearth. As far as his home goes, I suppose we can console ourselves that the facade of his house was actually saved. What Liverpool Street Station might not have finished off would almost certainly have disappeared in the Blitz.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you. Yes you’re right there it’s changed out of all recognition. I think there are a handful of buildings on the right of Bishopsgate that are pre war but not a lot else

LikeLiked by 1 person

My garndfather was brought up in that area, and certainly the whole neighbourhood round where his house would have been was razed to the ground in the war.

LikeLike